By Ane Liv Berthelsen & Rebecca S. Chen | January 23, 2025

What motivates you to carefully curate your data and code for a scientific publication? The concern that someone might uncover a mistake in your analysis and challenge your conclusions? The opportunity to showcase the quality of your coding skills? Or the possibility that others build upon your work or replicate your workflow?

Regardless of what motivates you, sharing your data and code by making it publicly available can be a catalyst for more rigorous, thorough, precise and more reproducible work. Knowing that your data and code will be open can encourage careful preparation and attention to detail before submitting your manuscript to a scientific journal, which likely also reduces the number of errors present in any analysis. After all, making honest mistakes is only human and detecting and correcting them an essential part of the scientific process. By embracing open data and code, we believe researchers can reduce the likelihood of preventable flaws and increase the detection and correction of inevitable mistakes.

We address the potential of errors to be corrected in the pre-publication stage in our Matters Arising article published in Nature Ecology & Evolution titled “Recognizing and marshalling the pre-publication error correction potential of open data for more reproducible science” (Chen et al., 2023). Our article is a response to Berberi & Roche (2022), who found no evidence that mandatory open data policies increased error correction in published research, a conclusion that advocates of open science might find unsatisfactory. Berberi & Roche (2022) identified three main barriers: 1) compliance to journal policies is weak and rarely enforced, 2) open datasets are often incomplete or hard to reuse and 3) journals are reluctant to publish corrections or retract papers.

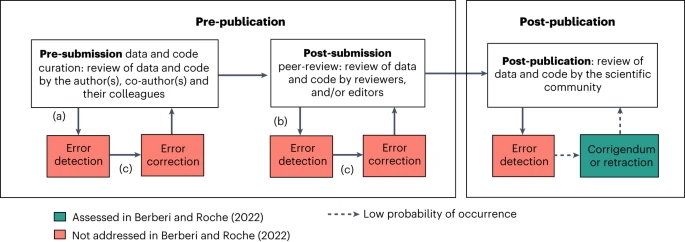

When discussing Berberi & Roche (2022) in the weekly Stats Club of Bielefeld University’s Evolutionary Biology Group, we realised that mandatory open data policies can very well have crucial effects in the pre-publication stage, which had not been considered by Berberi & Roche (2022). First, we expect authors to pay extra attention to how they curate and annotate their data and code during data analysis if they know the data and code will be made publicly available and can potentially be scrutinized during peer-review. Thus, fewer errors propagate to the submission stage. Second, reviewers will be able to assess the study design, statistical inference and robustness of the results better if data and code are available during peer-review. As a result, more errors are detected prior to publication. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the correction of detected errors is not only encouraged, but often mandatory during peer-review and comes without the stigma of post-publication error correction. Consequently, more detected errors will also be corrected. Our comment therefore highlights an alternative explanation of the null findings of Berberi & Roche (2022), as pre-publication error correction potential confounds the potential of errors to get corrected post-publication (Figure 1). More effective error correction during the pre-publication stage will decrease the power to detect effects of mandatory open data policies measured in post-publication stage.

Figure from Chen et al (2023).

In this blog post, we would like to put extra emphasis on the potential of errors to be corrected during the pre-submission stage, and the actions that can be taken to embrace this potential.

First, starting a new analysis with the intention to make your data and code publicly available upon publication should encourage an organised, well-structured analysis workflow right from the start. Not only does a well-organised workflow make the analysis more efficient and easier to re-run, it will also be easier to spot your own mistakes when all code is well documented and annotated. On top of that, it will save time preparing the data and code when submitting the manuscript, which can be a barrier to publishing code (Gomes et al., 2022). However, learning how to set up a well-organised analysis workflow – in our own experience – mostly gets done by trial and error. We therefore encourage the systematic teaching of how to set up a good repository for a project early in the training for a research career, ideally in the undergraduate stage, and at the latest when starting a PhD (using guidelines such as https://datadryad.org/stash/best_practices).

Second, we believe that fostering a working culture of sharing code, helping others with their code, and co-authors checking data and code in addition to results has a very high potential to correct errors during data analysis. Asking a trusted colleague to review and troubleshoot your code should not be considered a weakness nor a favour, but a part of the learning process and an opportunity to improve one’s skills, both for the reviewer and the reviewee (Gomes et al. 2022). Your colleagues likely have a better understanding of your data and analysis than a hired code reviewer does and can therefore help improve the analysis and spot mistakes in the code. Asking someone to be a second pair of eyes for your code also works as an in-house reproducibility test to ensure the code works on other devices and can reduce insecurity about sharing code and data that some colleagues experience (Gomes et al., 2022). Therefore, we encourage working groups and institutions to foster environments where discussing code, collaborating on data analysis, and helping others should be standard, as it can enhance the overall quality of the research.

We believe open data and code to be invaluable for many reasons, even if their full impact on the reproducibility and ultimately the quality of scientific output is difficult to quantify. Adhering to open data policies ensures transparency, reproducibility and reusability, which is key to making science more robust and reliable. Whether or not your target journal mandates open data, we think sharing data and code should be as standard as reporting the statistical models used in your analysis. To make this practice routine, it’s crucial to teach and encourage open data practices early in an academic career.

References:

Chen, R.S., Berthelsen, A.L., Lamartinière, E.B. Spangenberg, M.C., Schmoll, T. Recognizing and marshalling the pre-publication error correction potential of open data for more reproducible science. Nat Ecol Evol 7, 1597–1599 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02152-3

Berberi, I., Roche, D.G. No evidence that mandatory open data policies increase error correction. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 1630–1633 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01879-9

Gomes, D. G., Pottier, P., Crystal-Ornelas, R., Hudgins, E. J., Foroughirad, V., Sánchez-Reyes, L. L., et al. Why don’t we share data and code? Perceived barriers and benefits to public archiving practices. Proc Roy Soc B 289 (2022), 20221113. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.1113

Author Bios:

Ane Liv Berthelsen is doing her PhD project in molecular ecology at the Evolutionary Population Genetics group at Bielefeld University, Germany. Her work focuses on individual-based research and uses a Bayesian modelling framework to disentangle phenotypic trait variation in Antarctic fur seals. She addresses density related questions using anything from breeding colony images to genomic data. She is interested in open science and sustainability.

Rebecca S. Chen is a PhD student in molecular ecology at the Evolutionary Population Genetics group at Bielefeld University, Germany. She uses genomics and epigenetics to understand the genetic architecture of sexual trait expression in a classic model species for the study of lekking mating systems, the black grouse. She’s further interested in equity, diversity and inclusivity in academia and how open science practices can make research more accessible, robust and accountable.